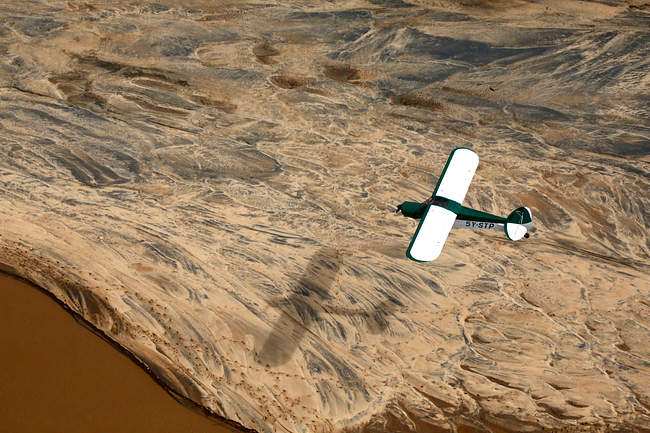

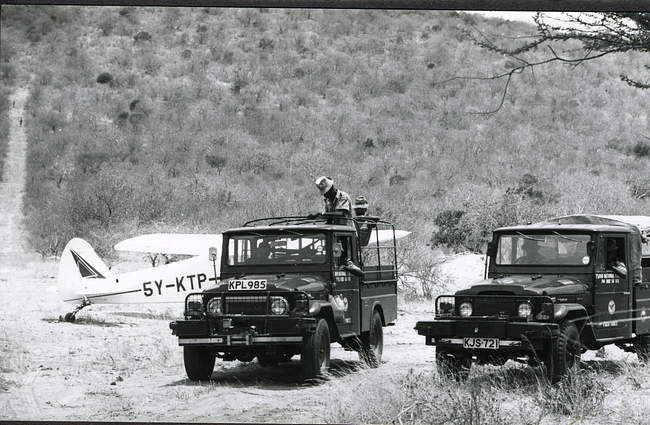

It is no surprise to us that the Super Cub is the aircraft of choice for conservation organisations across the African continent or that Kenya’s pioneer game wardens, David Sheldrick among them, believed that the Super Cub was one of the most important tools in conservation.

Warning: the claim made in the title may be subjective, however, we suspect there are a good number of pilots out there who would agree with us.

In fact, David Sheldrick believed so strongly in the abilities of the Super Cub -- and perhaps his own abilities as a pilot -- that he would often assert that a Super Cub could achieve anything a helicopter could (within reason). He demonstrated this on many occasions, being particularly well known at the time for landing his Super Cub in some of the most difficult off-airfield conditions. He would also, famously, slow down to a near hover and shout instructions out the window at his rangers – something only possible in a plane that can fly as slowly as a Super Cub and in the strong, steady winds often experienced in Tsavo.

Conservation has changed a lot since David’s time and there are many tasks for which a helicopter is better suited, such as darting injured animals, rapidly deploying rangers, and firefighting to name a few; however, the Super Cub still stands out as one of the most valuable tools in the conservationist’s workshop.

The characteristics, already alluded to, that make a Super Cub so useful are its ability to fly extremely slowly and its short take off and landing (STOL) capability. Add to this great visibility and the Super Cub is one of the most ideal planes for aerial surveillance. Sheldrick Trust pilots routinely patrol at just 60 mph. Because it is a relatively lightweight and the wings produce a huge amount of lift, it is also very safe at low altitudes, recovering quickly from a stall and having the ability to rapidly climb out of dangerous situations. Patrolling at between 100-300 feet off the ground, conservation pilots are able to spot all manner things.

An experienced Super Cub pilot can easily spot and photograph signs of human activity, from small campfires, to bicycle tracks, and even footprints if conditions are right. Injured animals can also be easily identified from a Super cub and the SWT’s Super Cubs have, over the last several years, located countless injured elephants (subsequently treated by SWT/KWS Veterinary Units), including ones with fresh arrow wounds where only the shaft of an arrow could be seen protruding from an elephant’s side.

Although a Super Cub is certainly not able to land everywhere a helicopter can, it is still able to land in incredibly small spaces and on relatively rough terrain, allowing pilots to drop off equipment and supplies to remote posts or mobile rangers and even extract injured rangers in an emergency.

One of the most remarkable stories involving a Super Cub in Tsavo concerns the successful elimination of a gang of Somali bandits that had been robbing tourists along the Mombasa highway. In 1978, Bill Woodley, another one Kenya’s original wardens, and at the time one of the best bush pilots in the world, flew ahead of a group of rangers that were tracking the bandits through the Park and away from Mtito Andei.

The use of planes can be instrumental in slowing the progress of suspects, forcing them to waste time concealing themselves. Bill eventually sighted the gang after they had crossed the Athi River and were heading up a valley that penetrates the Yatta Plateau. He soon began to hear the crack of incoming rounds caused by the bullets breaking the sound barrier as they passed the aircraft. Incredibly, he returned fire with a .303 rifle by holding the plane’s control stick between his knees and rotating right by 90 degrees, firing left-handed behind the rear strut of the right wing. He had also primed two grenades and dropped these from enough height to achieve an airburst, thereby blasting the shrapnel more efficiently. He killed at least one bandit this way.

Bill struck one of the bandits in the foot when shooting from the plane and while the bandit escaped, he didn’t get far; rangers discovered his body near the Athi River 6 weeks later.

The remainder of the gang were taken out by various means, from ambushes set by rangers along forward roads or trail chokepoints, and by the bandits’ Orma porters who speared them in vengeance for their heavy handedness on the way into the Park.

To this day, the valley where Bill Woodley courageously fought back against this heavily armed gang of Somalis is known as Hand Grenade Valley and serves as a reminder that even if the current generation of African bush pilots may not possess the same level of skill and bravery that he did, we are privileged to fly one of the most capable and reliable planes in the world.

Special thanks to Bongo Woodley for his help with the details of his late father’s heroic episode.