All the information put forward here is my understanding of this community as pieced together from the limited literature detailed already. Beyond these sources, most of what you are reading has been coloured by the Watha people’s own oral history as recounted to me via the filter of the individual Watha elders who told me. (Written by Gareth Roriston)

The Elder

The diminutive old man sits under the shade cast by a saltbush, atop a rucksack offered to him by me. He wears nothing but a kikoi skirt and a lifetime’s worth of weathered skin. As he sits, his toes curl into the coarse crabgrass of this green tenured patch of the otherwise semi-arid Tsavo biome and his healthy eye (the other whitened) dances from face to face of those gathered around him as he tells his tales of how he hunted elephants the way his people have since the dawn of history.

He talks of crafting enormous bows that even the strongest of men cannot pull without specific practice. He tells of poison tipped arrows and knowledge of the bush that is now drying up among his own folk, who are revered as masters of the wilderness by all who know them. He tells of the calls of golden tailed woodpeckers that will foretell how the hunt will unfold depending on which side of you they call from, how when he sees a mass of footprints, he can identify an individual animal and how he can decipher details about it.

He talks of the line of sight the elephants lack, how to approach them on the final stalk, the importance of being aware of the wind direction, which dictates what it can smell. He tells of where to place his arrow and when to let it loose. He talks of the times he was arrested and imprisoned, he laughingly recalls close shaves with charging bulls and matriarchs, he talks as if the elephants were people referencing peculiarities of character. He speaks with both familiarity and reverence for the totem animal of his people; his intimate relationship with the species and the land is self- evident.

He is a Watha, as such was born a hunter ...

The above details my first interaction with the late Badiva Wario Hirbai, a Watha elder back in 2010, where as Acting Warden of the Galana Wildlife Conservancy I travelled to Bombi and Kisiki Cha Muzungu villages (homes of the Galana Watha community) in the interest of community outreach for anti-poaching purposes. Since that day I have spent thousands of hours in their company, much of it walking in big game areas in an effort to absorb their bushcraft skills and, along the way, learning about their culture.

Very little by way of literature exists about the Watha. Chief sources I have found dedicated to them are: 'What I Tell You Three Times is True' (Ian Parker), an unpublished essay by the same author, 'The Elephant People' a.k.a People of the Bow (Dennis Holman) and an article entitled 'The Elephant People' in a February 1977 volume of Ecologist magazine. They feature heavily in 'The Shadow of Kilimanjaro' (Rick Ridgeway) and 'The End of The Game' (Peter Beard). Other than this, one may find references to them hither and thither in other books more as a side note to a broader narrative. These asides rarely give much detail about their culture other than to say they hunted and ate elephants and these days often poach them to sell ivory and are very, very good at it. In truth, even Dennis Holman’s 'The Elephant People/People of the bow' is less a description of the tribe and their culture as it is a biography of Bill Woodley (one of the early assistant Wardens of Tsavo East National Park) with the Watha providing the role of worthy and honourable antagonists in Bill’s tales of derring-do.

All the information that follows is my understanding of this community as pieced together from the limited literature detailed already. Beyond these sources most of what you are reading has been coloured by the Watha people’s own oral history as recounted to me via the filter of the individual Watha elders who told me.

Who are the Watha?

These days the Watha are a mysterious people, able to blend almost seamlessly with surrounding communities, yet still mostly marrying amongst themselves and retaining their own identity. When they do marry outsiders, these outsiders seem to 'convert' in a sense and take on the Watha traditions.

Not being recognised as an official tribe by the government during national census, they are counted amongst the numbers of neighbouring people often with whom they do not share even close ethnic ties such as with the Giriama who are of bantu extraction where the Watha are a Cushitic people. Nearly all the terms that the neighbouring tribes have come to use for the Watha have a pejorative if not outright derogatory meaning and it is by these names that most people know them: N'Dorobo (a Maasai term for any and all hunter-gatherer communities), WaSanye (used by coastal Swahilis and is believed to be derived from an old Arabic term for packing up one's effects, hinting at their nomadic lifestyle), WaLiangulu (a WaKamba term which means Tortoise Eaters. The Watha have a folktale explaining the origin of this epithet) and Boni (Boni means "cattleless" a Somali term for the lowest of castes).

Watha Origin Story

In the Watha oral history, they came down into the country we now call Kenya from the north in present day Ethiopia and, in some versions, crossed the Red Sea from present day Yemen. Somewhere deep in the mists of time they were a pastoralist people, a band of a larger group that went on to become the Orma, and Borana tribes with whom their language is a mutually intelligible dialect today. During this period there was a drought, which led to competition and war between these bands of common origin over water sources for their cattle. The Watha being few in number gave up the fight and their cattle and rekindled their not quite forgotten hunting and gathering skills to avoid annihilation at the hands of their enemies. 'Watha' is a contraction of a longer expression, which means 'to go with the will of god'. The sentiment being to live by one’s wits according to the whims of nature as opposed to the more controlled man-made order of raising one’s own livestock. They claim this benefited them as they became immune to the problems posed by pestilence and drought, which would periodically afflict their livestock-dependent neighbours.

The Watha retained ties throughout their history with the other Cushitic groups, especially the Orma. In their rendition of the migration south of the Cushitic peoples, it was the Watha who led the way learning the lay of the land via their hunting forays and informing their pastoralist cousins of water points and pasture when trading. They corroborate this narrative with evidence of places with names originating in their language from north to south. Malka Mari is a northern example. Sitting on the Kenya–Ethiopia border, “malka” refers to a watering point used by wildlife.

Traditionally an ideal place to ambush game. Tsavo is littered with place names in the Watha dialect - Aruba, Satao, Galdesa to name a few. Aruba comes from arrbe (elephant) the other two mean giraffe and baboon respectively. 'Galan' means river. Through Tsavo, the Athi river changes name to the Galana river. Going east toward the coast they claim Watamu and Dabaso as having Watha origins. If one were to say 'Watta moo' to a contemporary Watha, they would easily recognise it to mean 'he is not a Watha'. The folktale around the naming of the village is that, when the Arabs first arrived there, they would hear the local Watha say this phrase to each other, often during attempts at communication with them and eventually the Arabs referred to the area they had first contact with the Watha as 'Watamu'. Dabaso (an area close to Watamu) is a term for a species of long grass. Today there is a small Watha community living around Dabaso locally known as WaSanye.

It was Elephant that led them to Tsavo

For generations, the area we now call Tsavo East has been the ancestral hunting grounds of the Watha. I once asked my Watha friend Jefferson Guyo Badiva, 'Why Tsavo? It’s dry, it’s thorny, it’s pretty hostile. Of all the areas the Watha encountered along the migration, why did Tsavo suit them?' The answer was obvious: Elephants! Elephants were already a staple to the Watha at this time as they specialised and honed their focus on this big meat and resource provider. Tsavo was a bonanza of readily available prey. Traditionally a single elephant could feed a small family band of 20-30 people for roughly two months once processed. In intertribal economics, the Watha traditionally traded ivory and other animal products for cloth, salt and lamb which they considered a delicacy meat.

In the myth of one Watha clan, humans and elephants are related. In the story, a Watha hunter was preparing for a hunt. Impatient and tired of being left alone whilst her husband went out into the field to hunt, his cantankerous and pregnant wife warned him that if he did not return with a big game animal and plenty of meat to sustain them together for a while he should not come back at all lest he feel her wrath. Not being very successful, the hunter returned with only a dik-dik, scrub hare or warthog (depending on who is telling the story). The wife flew into a rage and a deep rumble emanated from her chest as she paced back and forth, then she let out a cry, both deep and shrill at the same time. She continued to scold her husband throwing her body into their hut, breaking it, and violently wagged her head from side to side, as she did this giant ears began to grow and flap, she stooped over onto all fours and grew. Her teeth extended into tusks, a trunk developed, which she threw into the air, trumpeted and charged away into the bush. Some time later she was seen with a calf, the unborn child within her during her transformation. Years later, an elephant family was seen by the hunter’s sons whilst hunting. They knew the story and assumed the calf and the mother had mated and produced offspring. The race of elephants was created. Knowing their history, the sons were reticent to kill their relatives. They returned to camp and informed the elders what they had seen. The elders concluded that the new species should be treated as a gift. The curse accorded to the cantankerous wife’s demands was that she and her children had become the very source of meat she had demanded, when raging at her husband for not returning with a big game animal. From then on, the Watha focused on the hunting of elephants, but always accorded them the due respect deserved of a relative.

With the arrival of capitalism and the free market during the 20th century, the resolve of members of the tribe was challenged regarding honouring the elephant in life and death, as some began to embark on a more commercial tack, motivated by selling ivory over meat consumption. Wastage became more common. Ironically, they say this increased when Tsavo East was gazetted as a national park in 1948. From their perspective, with the founding of the national park, their entire way of life was outlawed with an abrupt and confusing suddenness by external forces. They were eventually all informed about the government policy that there would no longer be any hunting permitted on their ancestral hunting grounds, but knowing no other livelihood and with the site of each kill now effectively being a crime scene, commercial ivory hunting yielded a safer and more rewarding option than camping by the carcass and utilising every morsel as had been the practice of the past, however “elatcha” (elephant fat) remained/remains a highly prized food source to those Watha willing to risk poaching. For some who did take the risk, pressure to make a living resulted in an inclination toward a volume approach to elephant hunting, slaying as many as possible and removing the tusks and a little “elatcha” as quickly as possible before being discovered by the authorities. This led to the entire community being complicit with the illegal ivory trade during the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s as their customary trade networks were driven underground. It was during this period that marginalisation and stigmatism of the tribe rose.

David Sheldrick, for his part in founding Tsavo National Park, and as the Warden of Tsavo East, had a love-hate relationship with the Watha. When David set about building a headquarters near Voi, with a lack of adequate surface water, he was forced to explore the option of a well along the Voi River near a place called Ndololo. During the early stages of the Park’s development, there were still a small number of Watha living within the Park in this area.

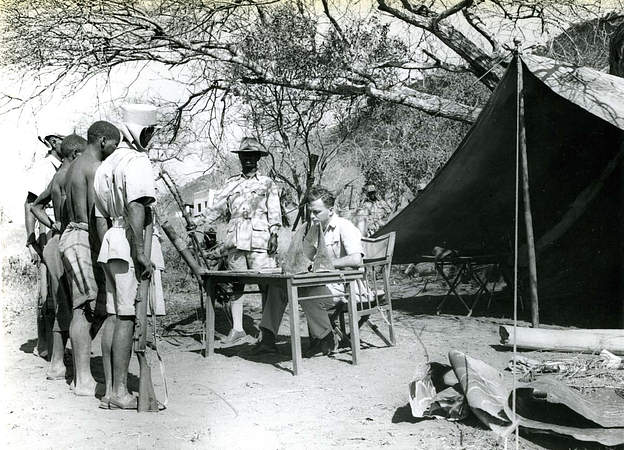

They lived across the river from David’s camp in a small settlement. This offshoot of the tribe had mixed with the local Taita people and, as Dame Daphne Sheldrick writes in The Tsavo Story, they were 'rather frowned on by the others due to their contacts with civilization and their liking for the bright lights of Voi.' On many evenings, the Watha men would wander into David’s camp and together they spent many a night around a fire, learning from one another. It was through these early exchanges that David and Bill Woodley were able to shed light on ivory trade. Showing little loyalty to the middlemen and the Arab traders on the coast who eventually sold the ivory on to markets in Asia, the hunters divulged a wealth of information, particularly about the mechanics of the ivory trade.

The Watha proved invaluable resources in many facets of the Park’s development and later management. They helped navigate the well-worn elephant paths that formed a mosaic, connecting seasonal waterholes, springs and rivers across an inhospitable landscape, and even formed part of the crew that would eventually transform these elephant paths into serviceable roads. Being excellent trackers, they also proved themselves among the ranger force, despite being reluctant to turn on and arrest their own. Later on, David would recruit heavily from the Northern tribes of Kenya, since they held no loyalty to local poachers and were similarly tough and bush wise. Unfortunately, the Watha never fully came to terms with a new identity that didn’t revolve around hunting. At one time, Bill believed that he had arrested every single male of the Watha community on at least one occasion.

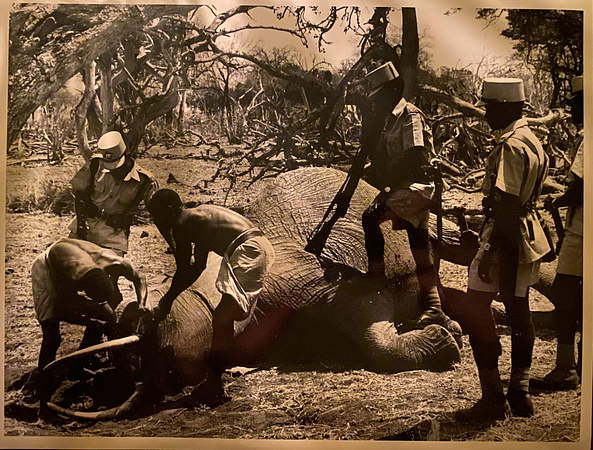

Much of David’s career was dedicated to the pursuit of one man, Galogalo Kafonde. To David he was a dangerous poacher, responsible for the deaths of hundreds of elephants, his work being easily identified by the trademarked arrows left behind in the rotting carcasses of his victims. Objectively, he was one of the greatest hunters that the Watha ever produced. To this day, he holds a sort of iconic status among the tribe, with many tales of his bravery continuing to be told.

For David, Galogalo’s capture was a tremendous relief. It was eventually estimated that he had killed a staggering 2,000 elephants during his hunting career. While tragic in the context of the elephant’s current status, and the knowledge that they were killed simply for their ivory, it is a testament to the skill of the Watha hunter. Perhaps no other people in history has been more adept at killing the world’s largest quarry, a skill which requires a profound knowledge of elephant behaviour and a courage borne of a supreme confidence in one’s own abilities when hunting with a bow and arrow.

Photographs courtesy of Wyn Herrick, the SWT and the Woodley family.