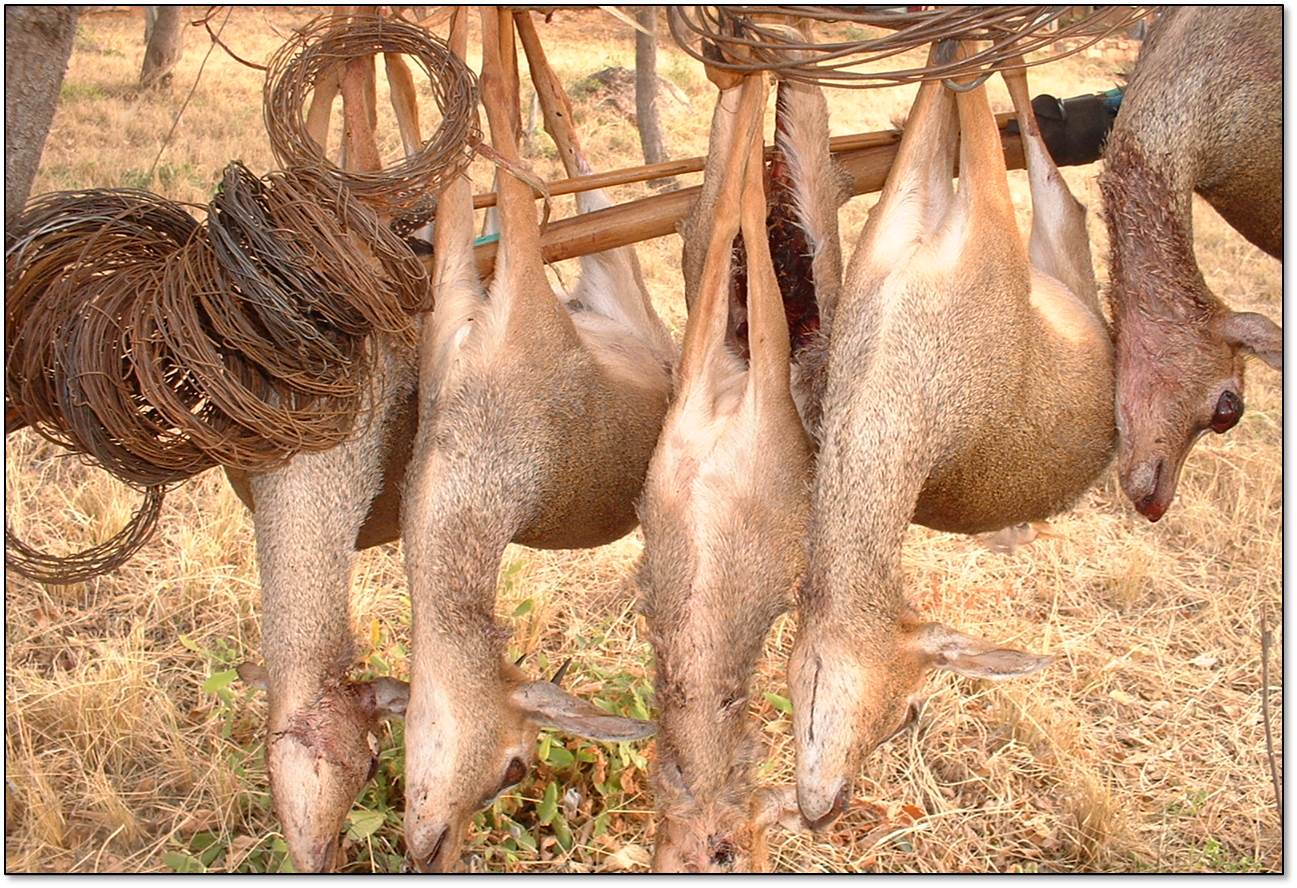

Snaring is a brutal way for an animal to die, since it is a slow lingering process accompanied by the terror of anticipating certain death, but sadly snaring is the most common method of poaching used by the hunters who supply the illegal bush meat trade in Kenya.

The Snare

by James Stephens

I hear a sudden cry of pain!

There is a rabbit in a snare:

Now I hear the cry again,

But I cannot tell from where.

But I cannot tell from where

He is calling out for aid!

Crying on the frightened air,

Making everything afraid!

Making everything afraid!

Wrinkling up his little face!

And he cries again for aid;

- and I cannot find the place!

And I cannot find the place

Where his paw is in the snare!

Little one! Oh, Little One!

I am searching everywhere!

Snaring poachers work alone or in small groups, camping out in the bush for days at a time, trapping and skinning small antelope and drying their meat in the hot sun to preserve it. They are capable of setting hundreds of snares along animal tracks and near watering places within close range of their bush camp.

In the simplest terms, a snare is merely a noose fashioned out of wire, string or cable and suspended around an animal’s path. Generally, it is set at a specific height and size so that it can easily slip over the head or foot of its intended prey. As the animal fights to free itself, the noose tightens suffocating the panicked animal if it is around the neck, and causing a deepening wound, if around a foot. The more the animal struggles, the tighter the snare becomes, cutting into flesh; and when the snare entraps the leg, foot, or waist of an animal, it can penetrate through to the bone before the animal finally dies.

Even elephants are snared but with a much larger and stronger wire in order to be restrained. In their case, a length of heavy cable, usually stolen from a power line, is anchored firmly to a large tree or in some cases a large rock, with the other end set to slip over the elephant’s foot or head. Once it has been caught and restrained, the poacher, using either a poisoned arrow or a spear can easily kill the elephant. In some instances the terrified elephant, now tethered to the tree, will crash around in circles levelling everything within reach before finally collapsing of exhaustion. Poachers take great pains to select a suitable site for an elephant snare because whatever the cable is attached to must obviously be sufficiently strong to restrain an animal that weighs several tons. A cable set at head height must be carefully concealed so as not to alert the elephant to its presence so leafy branches are often woven around it to conceal it and make it less obvious. Branches may also be suspended above the path. Should the poacher aim to snare the leg, a rocky site in descending and difficult terrain will be selected to ensure that the elephant has to pass that way, confidently predicting exactly where it will be placing its feet.

As with all snares, cable snares are indiscriminate and are capable of trapping young elephant calves as well as adults. Some may manage to escape but will be wounded and will inevitably fall behind the herd as a result of their injuries. The lucky ones are discovered before it is too late and can be rescued as orphans, hand-reared at the Trust’s Nairobi Elephant Nursery and ultimately rehabilitated back to a wild life when grown. However, since elephants are milk dependent for at least the first 3 years of life, and partially so until the age of 5 years, having lost a mother, a milk dependent orphan will not last long without access to milk and the protection of the herd.

A spring snare, though more labour intensive to set up, is more effective. A bent sapling forms the spring and is held down by twine anchored by a trigger mechanism next to the animal path. The noose is attached to the trigger so that as the animal slips through, the spring is activated and the animal is hoisted off the ground, simultaneously tightening the noose. As with simple snares, spring snares can target a huge range of prey and are inexpensive to construct since mere sisal string can be used to catch game birds such as guinea fowl and yellow-necked spurfowl, as well as small and even medium sized antelope such as impala and bushbuck. Substituting string with rope enables even larger game such as buffalo to be targeted. In some cases the noose is laid over a shallow, covered pit so that when the animal’s leg breaks through the cover of the pit, it slips through the noose, and the spring snaps the knot tight around the leg.

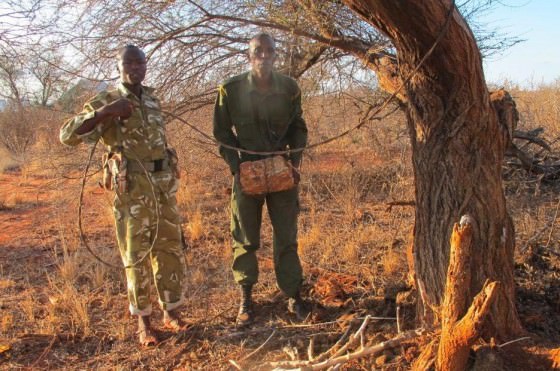

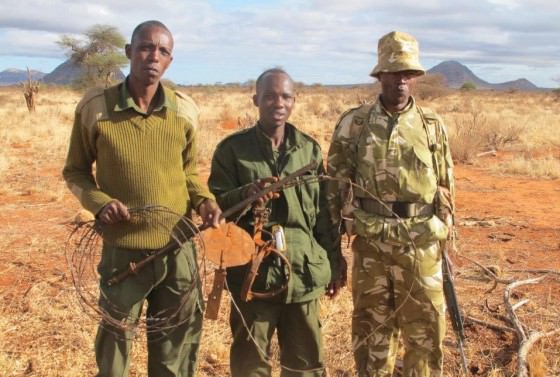

In 1999, the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust established its first de-snaring team, tasked with removing these deadly snares before they claimed precious wild lives. Since those humble beginnings, with just one team operating in Tsavo East National Park, 114,000 snares have been retrieved and confiscated. Today, the Trust has seven teams patrolling a large chunk of the Tsavo ecosystem on foot along with armed KWS Rangers. They investigate the web of animal tracks that crisscross the rugged terrain, cutting through thick Acacia and Commiphora woodland towards rivers and waterholes. The patrol is alert to any indication of illegal human activity such as footprints, bicycle tyre tracks, cut branches etc., which might indicate the proximity and presence of poachers. Following any such signs radically increases the chances of detecting snares and controlling other forms of illegal activity.

With persistence and dedication, the de-snaring teams work hard to make it as difficult as possible for poachers to be successful. Whilst the National Park is too extensive to be able to effectively patrol on foot in its entirety and even were this possible, it would be impossible to find every single snare. Nevertheless, disrupting the ability of poachers to take a toll of wildlife does have a significant impact and certainly dissuades many would-be poachers from engaging in an already challenging career where the risks might outweigh the reward, particularly now that punishments for poaching offences have been greatly enhanced. Already, during the years the Trust’s de-snaring teams have been operating, there has been a marked gradual decrease in the number of snares being found and hopefully over time this is a trend that will continue.

If you would like to learn more about DSWT operations in Tsavo you can do so here: http://www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org/desnaring/index_new.asp