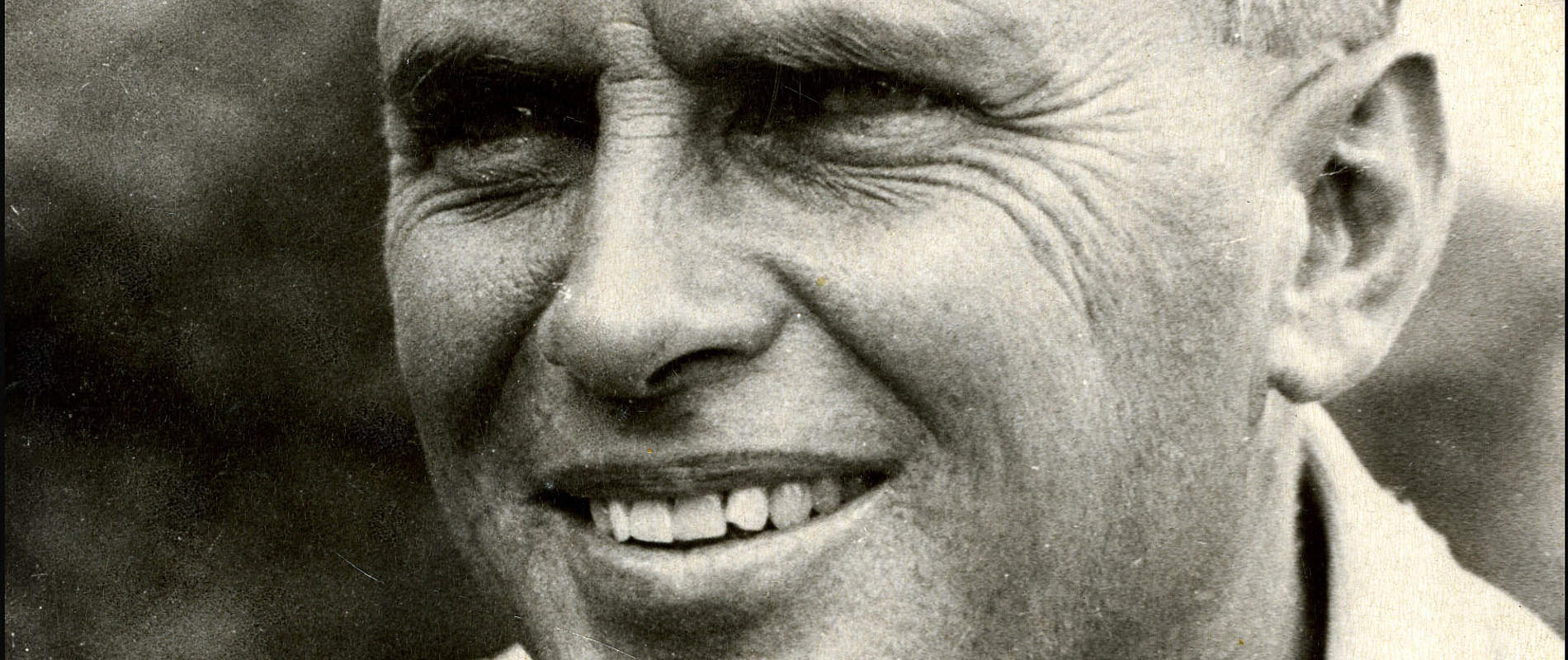

The Sheldrick Wildlife Trust is built on a legacy of conservation, beginning with one man’s visionary plan for Kenya’s wild spaces. Even today, David Sheldrick stands out as one of Africa's most famous and proficient Pioneer National Park Wardens of all time.

In 1948, at the age of 28, he was given the challenging task of transforming a huge swathe of uncharted land into Tsavo, Kenya's largest and most famous National Park. Metamorphosing the inhospitable wilderness, which covers an area of just over 5,000 square miles — equal in size to Michigan state, Israel, or Wales — was a prodigious task, but David persevered. He was the park’s first Warden, a post he held until he was transferred to lead the Planning Unit for all Kenya's National Parks and Reserves, at the end of 1976. David died just six months later, but the legacy he left endures.

David’s notes heavily influenced The Wilderness Guardian, which is a textbook used by most wildlife institutions across Africa and an integral part of every Field Warden's library. In the Author’s Note, Tim Corfield pays homage to David with a wonderful summation of his character:

“How can I adequately portray this remarkable man and his achievements? The strong, handsome, weather-beaten face, the hard blue eyes, the powerful frame and large competent hands; the courteous manners, keen sense of humour and clear perceptive mind; his quietness, willpower and endurance, his deep underlying compassion and above all his integrity. To say that he is the finest man I have ever met is inadequate, for what is my experience as a yardstick. I can assert that he was a truly great man; but such a cliché; sheer over-use has blunted the impact of so many powerful words and descriptions. I state simply, then, that in Tsavo National Park a man of quite exceptional stature imposed his will on men and machinery to preserve one of the world's great wildernesses, and thereby set a pattern of development for Kenya's National Parks that was to be the envy of the world. In a tragedy I outline below, this task killed David Sheldrick, but in his death he provided for us immeasurably, both in the systems he left behind, and also in the example of his fight to create a real wilderness sanctuary - not a glorified game ranch, not a Zoo Park, not a scientific experiment nor playground, but an area where wilderness could simply be. Central to his efforts was a belief that wildlife and wilderness were not to be guarded simply for their own sake, but they were a well-spring for our spiritual refreshment - yours and mine and that of future generations.

He had spent time - snatches of it and long unbroken stretches in the quiet company of wild animals and he had learnt to observe and study them with sympathy and understanding, not in the superior and arrogant manner of the Scientists chalking up knowledge, but with the humility and empathy of a born naturalist. His alert and enquiring mind was finely tuned to the complexities of Nature, and the time he spent quietly absorbing her ways engendered strong convictions and a deep underlying confidence in her. This, as much as anything else, fuelled his dogged defence of a natural solution to Tsavo's much publicised "elephant problem" (in the early seventies). There were expedient options open to him which would have appeased the critics of his policies, but David Sheldrick knew that to take these would be an abrogation of his duty both as a Warden and a man. His resolve, then, to protect the wilderness was absolute, and he turned resolutely away from embarking on any precedent that could prove dangerous or lead to abuse, thereby jeopardising the sanctity of the Park he had created and loved so completely."

It is comforting to know that, all these years later, the foundations David built continue to inform the practical field work of the Trust. Working closely with the Kenya Wildlife Service, we continue his mission to preserve our country’s precious natural heritage. This we achieve through our Orphans Project, Anti-Poaching Initiatives, Mobile Veterinary Units, Saving Habitat Programs, Community Outreach, and direct support for the Kenya Wildlife Service.

Our conservation work has fostered a more compassionate understanding of elephants and Kenya’s wild places. More and more people appreciate just how precious it is — and how quickly it can all disappear were it not for our hard work in the field. David Sheldrick was truly ahead of his time in this regard, and Daphne only further cemented all that he began and earned her very own place in Kenya’s conservation history. It is a privilege to be able to continue all that they began.

Nothing brings home how deeply we are linked with our history than stories like this one, with the photographs shared above: In the early 1970s, a young elephant became hopelessly stuck in the drying mud of Kanderi Swamp during the drought in Tsavo. The herd lingered close by desperate and helpless. David and his team were responsible for saving this young life, along with the lives of literally thousands of other elephants over the decades that he and Daphne were in Tsavo. David’s anti-poaching teams were the finest in the land, with very many thousands of hours flown in this trusted super cub in support of his field teams, his veterinary efforts were pioneering in their approach, and his practical field knowledge and expertise remain unsurpassed. This combination enabled the vast expanse of Tsavo to be forged into the famous National Park it is today. We continue and build upon David’s legacy, working closely with the Kenya Wildlife Service in our lifesaving efforts that he began all those years ago. Similar stories to that of the elephant in Kanderi Swamp unfold every day, and we will continue to save and support thousands of wild lives every year.