A hotbed of volcanic activity in the past, Kenya’s remote Tsavo ecosystem offers some of the most dramatic landscapes in the world.

The impact of this landscape can be appreciated by simply driving down the Nairobi-Mombasa Highway, which bisects Tsavo and forms the boundary between Tsavo East and West National Parks. However, one cannot fully comprehend the magnitude of this remarkable place until taking to the air over it. Roughly the size of Wales, it would take days to cover in a small plane.

For the purposes of patrolling, the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust pilot usually limits his activity to areas most threatened by humans. Signs of human activity may vary. Herdsmen leading cattle into the National Park to graze will often erect temporary paddocks using cut branches, arranged in a circle, into which cattle are herded at night. These are easily visible from the air and offer the first clue that people have been in an area. If people are found grazing livestock within the boundary of the park it is reported immediately to the Kenya Wildlife Service, for only in rare circumstances is this legal. Not only can overgrazing be detrimental to the fragile ecosystem that exists in Tsavo, but poaching seems to go hand-in-hand with any form of human presence in an area.

Poachers come in many shapes and sizes, as poaching methods vary depending on the intended prey and the resources available. Because of this, a pilot is looking for a broad range of signs of illegal activity. Some poachers enter the park on foot and set small snares to catch small to medium-sized antelope, which can be dried in the field and later sold to the illegal bush meat trade. Poachers in search of larger game such as elephant will use anything from large cable snares, poisoned arrows, to automatic rifles. A pilot might spot a shooting platform or blind from the air, which will usually be located near a water source to increase the poacher’s chances of capture. Additionally, poachers that spend several days in the bush will often have cooking fires along with cooking utensils, which if the pilot is lucky will reflect the sun's light toward the aircraft. Essentially, the pilot is looking for anything out of the ordinary. Poachers will sometimes use bicycles or motorbikes to enter the park, for example, which leave distinct tyre tracks in the dust that can be seen from above.

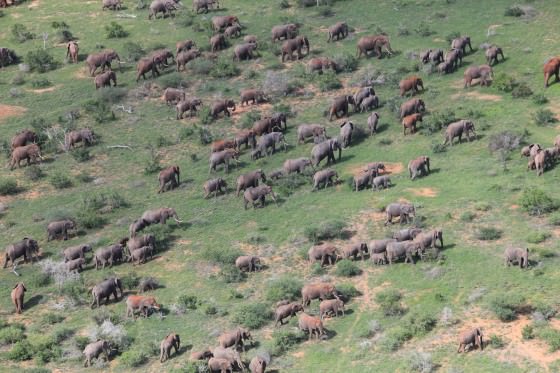

Another function of the SWT's aerial surveillance unit is to build a useful Geographic Information System (GIS) database, which will be used to continually improve the operations of the SWT and its partners. Recorded information includes GPS locations for animal carcasses (along with suspected cause of death), live animal sightings and numbers, locations of poacher's shooting platforms as well as recovered paraphernalia. The expectation is that over time patterns will emerge and decisions regarding what areas need the most attention will be better informed.

The practice is not a new concept, of course. Even in the ‘60’s, David Sheldrick, who spent much of his time in a plane himself, meticulously recorded his own sightings. A large map in his conference room with a metal back allowed him to move coloured magnets around to display information such as large concentrations of various animals which he saw from the air (elephants, buffaloes, etc.). Today, however, modern technology in the form of GPS and GIS software make the task more efficient and a much more powerful tool.

The reward for this diligence is the protection of one of the most beautiful spaces on earth including the animals that make it come to life. It is apt that in return for his service the SWT’s pilot be afforded such truly spectacular views. Taking off from the Trust’s main airfield in Mtito Andei, the plane is first lifted over the Yatta Plateau. This ancient lava flow is the longest in the world. Flowing 290 km from Ol Doinyo Sabuk Mountain it now runs along with western boundary of the park next to the Athi River. Behind and to the West, the undulating Chyulu Hills, topped with a dense cloud forest, frame Mt. Kilimanjaro, which on a clear day rises magnificently above the horizon. As the plane passes over the Yatta Plateau, Tsavo East is unveiled ahead. Its relatively flat terrain offers stark contrast against the hundreds of rocky hills, kopjes, and granite outcrops that are scattered randomly across this arid expanse. The scarcity of water that makes Tsavo so inhospitable becomes exceedingly apparent from this vantage point. Aside from the Galana and Tiva rivers, the only sources of water are muddy waterholes (many of which dry up for the majority of the year) that dot the landscape. Connecting these waterholes is a labyrinth of meandering animal tracks.

As already mentioned, the two main rivers in Tsavo East are the Galana (in the South) and the Tiva (in the North). The Galana begins its journey as the Athi River near Nairobi, but changes designation where the Tsavo River joins out of Tsavo West National Park. From this point it snakes across the Tsavo Conservation Area before finally emptying itself into the Indian Ocean. The river can be identified from miles away by large trees and doum palms that line its banks. Where the river slows to move around rocky obstacles, large, beautiful, white-sand beaches form where the current slows, creating lovely, unique scenes at every corner. Annual flooding, though becoming less and less reliable, can alter these beaches overnight, displacing hundreds of tons of sand. So even though the general shape of the river may not change dramatically, its appearance often does.

The Tiva River on the other hand is seasonal and usually characterized by miles of exposed, white-sandy river beds. Pools of water are sometimes left behind from the last time the river flowed, but in the absence of these, elephants will move along a seemingly dried up river detecting moisture with their sensitive trunks. Where the water is closest to the surface they excavate large holes using their tusks to access the water below.

It should be noted that when it rains Tsavo becomes almost unrecognisable in a matter of days. Rivers swell and appear out of nowhere and the once grey dusty landscape becomes shrouded in thick green foliage and showered with white and pink ipomea flowers. Depressions fill with water and lakes cover huge areas. To the East, where the Park borders Galana Ranch, large tracts of poorly drained black cotton soil quickly saturate to form clay that can preserve the footprints of passing elephant herds for months, and are clearly visible from the air. The desert becomes the jungle and Tsavo proves that its beauty is dynamic. It reminds us that it is a theatre of gigantic proportions.