In early February 2014 the Kenya Wildlife Service is committed to an aerial count in the Tsavo-Mkomazi Ecosystem, which was last done three years ago

In early February 2014 the Kenya Wildlife Service is committed to an aerial count in the Tsavo-Mkomazi Ecosystem, which was last done three years ago. This census is scheduled to begin on the 3rd of February and is estimated to take seven days with a minimum of 18 aircrafts supporting the effort.

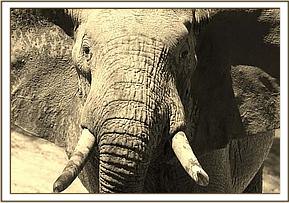

The area includes Tsavo East and West National Parks in Kenya and Mkomazi in Tanzania, along with an area the same size again of rangelands, and is the country’s most important elephant sanctuary.. This is not only because it holds the country’s single largest population of elephants with the space to afford them that essential elephant aspiration, which duplicates that of us humans – a quality of life. It is an arid Animal Kingdom, home to a greater diversity of species than any other Park in the entire world, since it is where the Northern and Southern races of fauna just happen to meet, thereby duplicating many species.

Having been developed from pristine arid and forbidding wilderness hitherto simply known as the “Taru Desert” by the late David Sheldrick, it is here the Trust, established in memory of David, mainly focuses its conservation support. It was home to David from l948 when the Park was first proclaimed and its boundaries were established, and home to Daphne from l955 until David was transferred from Tsavo to head the new Wildlife Conservation & Management Department’s Planning unit in 1996 in Nairobi. David always maintained that it was more likely to survive Kenya’s burgeoning population pressures due to its inhospitable semi desert environment and the fact that there is no better form of land use for the area than under tourism and wildlife.

Next month in February 2014, another census of the Tsavo Elephants is to be undertaken, and the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust is not only providing all the aviation fuel necessary for this count to be undertaken, but is also providing the use of its 4 aircrafts in order to help in this challenging exercise. Each aircraft will set off early in the morning to conduct 1km spaced transects across designated blocks of up to 900 km² (some are smaller). Most aircrafts are expected to fly an average of 7hrs per day over the 5 days of counting. This census is in view of the poaching that has taken place throughout Africa of late, driven by the demand for ivory from the Far East, and particularly China.

Tanzania’s Selous National Park was once home to East Africa’s largest population of elephants – estimated at over l00,000 in 1976 which now stands at a mere 13,000 according to the latest reports, some 30 elephants estimated to have been killed every day in recent years since the Chinese population became more opulent driving the demand for illegal ivory, which has pushed up the price paid to a poacher a thousand fold.

Tsavo’s Elephants have weathered many threats and continue to do so. It was entirely due to David Sheldrick that Tsavo East exists as a Protected Area today, since the first Director, Colonel Mervyn Cowie wanted it abandoned, believing that its hot, flat and arid terrain was unsuitable for tourism compared to the picturesque aspect of Tsavo West. David fought for its survival, arguing with authorities that it was Tsavo East that held the female breeding herds of elephants, as opposed to Tsavo West which was then mainly inhabited by Bulls. He won that battle.

He then again fought furiously for the elephants when it was considered that there were too many and that they were desecrating the commiphora thickets and turning the Park into desert. It was believed therefore that they would have to be artificially culled South African style. Ahead of his time, David had undertaken his own thorough research and was able to argue, again with authority that the elephants were merely doing what elephants were designed to do, changing arid scrubland into grassland as the process of a long-term natural cycle essential to preserve the grazing species of the Park, and that far from destroying the environment, the elephants were improving it by transforming commiphora thicket into grasslands that would ensure the survival of the grazing species - they are the Gardeners of Africa, and without the elephants and the vital role they play many species would be lost forever.

The elephants themselves would then experience a natural “die off” having planted a new generation of trees in their droppings during their long-range travels. Again, David Sheldrick was proved right and won that battle. He could foresee how the elephants could be compromised by corruption whereby the Ranger Guardians might be tempted to become killers, and that an expanding human population would begin to deprive elephants of much of their habitat beyond the Protected Areas, and cut off ancient migratory corridors elephants had trodden for millennia and bring them into conflict with human interests.

Being a Naturalist of note, he believed that Nature would adjust to any over-population in its own way, and that natural selection, whereby the weak, the sick and the maimed would be removed first, was the best way since it ensures healthy survivors to breed up the population for the future. David was also the first person to recognize and understand the very human aspect of Elephants, since he rescued orphaned elephant babies in the early fifties, whom he reared and who simply returned to a wild life in their own time and at their own pace. Through the work of The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, this has been proven over and over again over many decades.

The Tsavo ecosystem, an area that covers Mkomazi (in Tanzania), Tsavo West, Tsavo East, Chyulu Hills National Park, South Kitui National Reserve; Taita ranches; Galana Ranch 46,437 square kilometers (Tsavo East and West National Parks occupy an area of about 21,000 km²) once held a scientifically estimated elephant population of 45,000. A severe drought of the early seventies naturally “culled” more elephants than the l0,000 the scientists wanted to kill artificially, the difference being that nature did it much more humanely, through malnutrition as opposed to slaughter, malnutrition being the natural end for an elephant when its sixth set of grinding molars is warn out. It was all over in less than 3 months, unobtrusively and quietly, nature targeting the females and their dependent young, which ensured the generation gaps necessary to put a population in decline and relieve the pressure on the land to allow the new generation of trees planted by the elephants to regenerate.

Following the death of David Sheldrick in l977, rampant poaching of elephants for their ivory tusks took hold, and the guardians of the elephants did, indeed, become the killers. Over the next two decades poaching reduced the population of the Tsavo ecosystem to a mere 6,000, until the l989 total Ivory Ban imposed by CITES brought about a brief reprieve. However, the ban did not hold for more than one generation of elephant young to be born before CITES then sanctioned the selling of the Southern African so-called legal stockpiles, authorizing China along with Japan to be the buyers. However, the Tsavo population did recover, by 2008 they had recovered to 11,696 and then the elephant population in the last count of 2011 stood at 12,572. Since then poaching for ivory has escalated to an unprecedented level in recent years, so this count will be extremely important to see where the population stands today.

The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust is proud to have continued the legacy of the late David Sheldrick and proud to play a significant part in supporting the Kenya Wildlife Service by helping to protect Tsavo and its remaining elephants, amongst whom live almost 90 of the elephant orphans hand-reared from infancy by the Trust who are now living wild amongst that community.